The Weddell Gyre

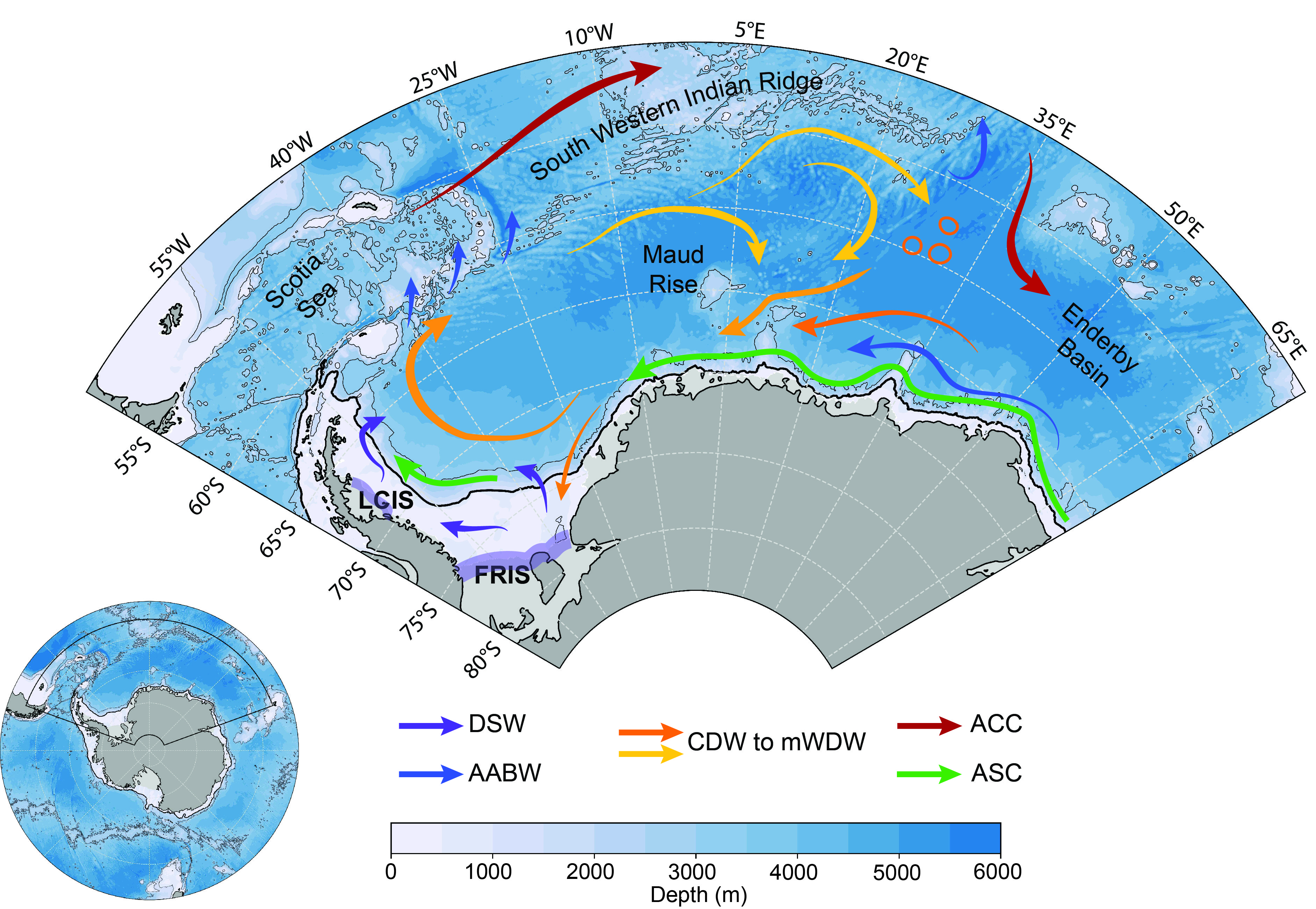

The Weddell Gyre is located east of the Antarctic Peninsula, a region that despite its remoteness, plays a major role in Earth’s climate. The gyre is a permanent feature of the ocean circulation, comprising a huge clockwise vortex that moves between 20 and 100 million cubic meters of water per second and brings relatively warm waters south close to the Antarctic margins. The uncertainty in the gyre’s volume transport speaks of the difficulty of obtaining oceanographic measurements in a region characterised by extensive ice cover throughout most of the year.

Ocean gyres are a well-known feature of our oceans, but subpolar gyres like the Weddell remain poorly understood compared to their subtropical counterparts in the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. Traditionally, gyres are assumed to be driven by surface winds, which impose a frictional stress at the surface of the ocean that is able to move the upper thousand meters or so of the water column. In the Southern Ocean, the presence of sea ice modulates the frictional stress set by the winds, and perhaps for this reason previous studies have failed to find a relation between the stress at the surface and changes in the Weddell Gyre’s strength.

Ocean gyres are a well-known feature of our oceans, but subpolar gyres like the Weddell remain poorly understood compared to their subtropical counterparts in the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. Traditionally, gyres are assumed to be driven by surface winds, which impose a frictional stress at the surface of the ocean that is able to move the upper thousand meters or so of the water column. In the Southern Ocean, the presence of sea ice modulates the frictional stress set by the winds, and perhaps for this reason previous studies have failed to find a relation between the stress at the surface and changes in the Weddell Gyre’s strength.

This uncertainty is a problem, because we believe the gyre’s strength is involved in climatically relevant processes. For example, at the south-western Weddell Sea, the Filchner-Ronne Ice Shelf is producing large amounts of dense water, that sinks into the Weddell Gyre and travels north within its circulation. The formation and sinking of dense water acts as a pump, powering an overturning circulation that is key to the absorption and storage of heat and carbon, and the Weddell Gyre is involved in exporting these dense (now abyssal) waters northwards into the global ocean.

So, what makes the Weddell Gyre accelerate/decelerate? In my last project during my PhD, I tried to answer this question by making use of a theoretical framework combined with model simulations. I applied some very simple perturbations in the model that forced a change in gyre strength, and then I used an equation that contains the physics of fluid motion to try to identify the “culprit” force that had changed the strength of the gyre. I found that the presence of a dense water overflow at the bottom was frictionally “arresting” the gyre from the bottom-up. Imagine going on a slip ‘n slide, but instead of soap and water it was covered in peanut butter. The increased friction from peanut butter would make your sliding speed decelerate.

This analogy is not exact, because the increased friction of peanut butter comes from its viscosity, whereas the increased friction at the bottom of the Weddell Gyre comes from the speed of the dense water spill. But it is easy to see now how a more intense bottom current could slow the gyre down via increased bottom friction.

The real world is a bit more complicated than the simulations I used: instead of one isolated perturbation there are multiple forcings going on at the same time, nudging the ocean circulation one way or another, over a variety of time-scales, making the physical processes and their effects really hard to disentangle. But the experiments I undertook highlight a new process that seems to be important in the Weddell Gyre – something we did not know beforehand, contributing to our understanding of the ocean dynamics in this region.